Access Denied

Despite signing UN treaty on rights of persons with disabilities, Pakistan far from making its infrastructure inclusive

By Ferya Ilyas

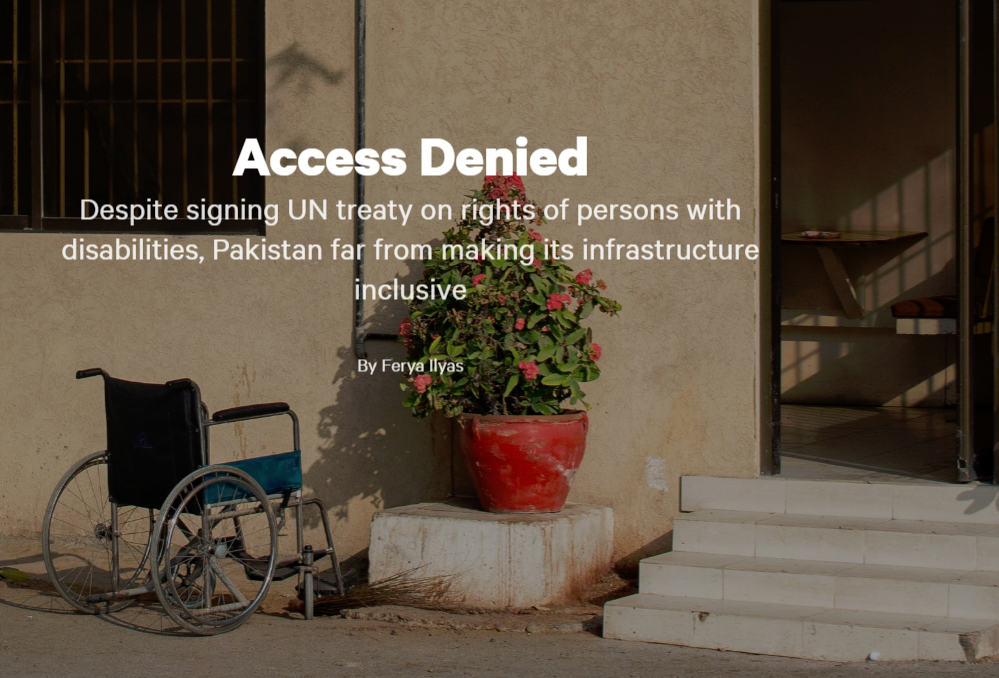

The line at this NADRA office stretched outside the narrow entrance, and there were no ramps to accommodate people with disabilities. PHOTO: ZORAL NAIK

Structures of the state

Having struggled with movement all her life, Rasheed says lack of access to buildings is a major hindrance for people with disabilities who want to live a regular life. “Personally, I don’t go to places that don’t have proper access, and that is 80% of all places,” she says. “I don’t go because I don’t want to be lifted and transported by others.”

An MBA graduate and marketing professional, Rasheed is the force behind the Show You Care (SYC) initiative which aims to create acceptability and increase accessibility for people with disabilities. “Accessibility is not a ‘favour’ or special treatment; it is a basic human right,” Rasheed reiterates.

Speaking about government buildings in Pakistan, Nabil Shaukat, Program Manager at Network of Organizations Working with People with Disabilities, Pakistan (NOWPDP), says the structures are nowhere close to being accessible for people with disabilities. “In Pakistan, many government buildings are rented or taken up properties post-Partition, which don’t allow access to people with disabilities, specifically persons with lower limb physical impairment, which is the most common of all disabilities in Pakistan. Certain buildings are built in such a complex manner that they cannot be made accessible unless demolished and re-created,” he says.

The sketch depicts how this facility could have been made accessible to people with disabilities. PHOTO: ZORAL NAIK; ARTWORK: AAMIR KHAN

Misbah Ali, a building control officer with Sindh Building Control Authority (SBCA), agrees. “Very few new government buildings are constructed and the old ones were built long ago; they can only be readjusted to accommodate the needs of people with disabilities,” she says. For her two years of service at the department, Misbah says she has personally not come across a single proposal for making an old public office building accessible.

The irony here is, NOWPDP’s Shaukat says, that the very department – Social Welfare Department, Sindh – which caters to persons with disabilities in Karachi doesn’t have a ramp of the right proportions. “Access for people with disabilities is the last item on the list for most people and for some it is not even on the list,” Shaukat laments.

A visit to the department confirms the claim. The building, located between the Supreme Court Registry and Arts Council, has surface-level but broken pavement at the main entrance. The pathway from the main entrance to the actual office compound is smooth but the gate leading to the office compound has a steep ramp. There is also not enough space for a wheelchair to move easily from the gate to the offices, with manholes and other concrete structures blocking the way.

Riaz Fatima, the department’s deputy director, says they are aware of the inadequacies and will make sure the building’s accessibility is in line with universal standards. “We have special instructions from Minister Shamim Mumtaz to provide facilities to people with disabilities,” she says. “We have written letters to Works and Services and Zakat and Ushr departments, recommending the construction of ramps in office buildings as well as mosques. Our target is to make all the 18 centres of our department across Sindh accessible before the end of this year.”

D J Science College in Karachi did not have any ramps around the main entryway. Our sketch shows how the structure could be easily modified to cater to the needs of people with disabilities. PHOTO: ZORAL NAIK; ARTWORK: AAMIR KHAN

Codes and concrete

According to the NOWPDP official, Pakistan has a standard accessibility code developed specifically for persons with disabilities and must be applied to all public and private infrastructures. “But because of lack of checks by the government, the compliance and implementation of these standards have been neglected,” he shares.

Dr Noman Ahmed, chairperson of NED University’s Department of Architecture and Planning, says the most commonly followed building law – Karachi Building and Town Planning Regulations – in the country’s biggest city outlines in detail the general conditions and provisions needed for making structures inclusive. He, however, says there are big gaps when it comes to implementation of those provisions. “When buildings are made, there are aggressive checks for entry points and emergency exits but not so much for accessibility provisions,” he states.

This ramp outside the NADRA office at Awami Markaz in Karachi was a good example of a facility that serves persons with disabilities. PHOTO: ZORAL NAIK

According to Dr Ahmed, most developers argue that if a building has an elevator, it is accessible to people with disabilities because they can move vertically as envisioned in the accessibility codes. “But once these buildings are in use, these provisions stop functioning due to lack of maintenance or power outages. Lifts in many public buildings stop working and are never made operational again,” the professor says.

When approving designs for new structures, Dr Ahmed says the building control authority inspects plans based on the information provided by the developers, who make sure not to submit anything which might get the project struck down. “Sadly though, these plans are changed considerably during the construction phase and the control authority fails to review the constructed building against the approved design,” he says.

This building of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Pakistan in Karachi has a ramp but no railings and a steep inclination. PHOTO: ZORAL NAIK

Misbah from SCBA corroborates the assertion. “I have been working here for two years and our department has never issued a ‘No Objection Certificate’ for a project that violates rules. The fact that we don’t have accessible buildings is because approved plans are changed over time,” she says.

According to her, building plans are reviewed carefully in light of regulations for access, recommendations are made for inadequacies and violations are noted once the project is complete. Misbah says if changes are not made to the structure, the building authority files a case in court and depending on the verdict, the builder either makes the changes or SCBA demolishes the portion.

A building control officer, who did not wish to be named, says this is the standard procedure but in reality, regulations are violated at various stages and the enforcers turn a blind eye for their own interest.

The main building of DJ Science College had a staircase leading up to the classrooms, but no facilities for people with disabilities. PHOTO: ZORAL NAIK

Beyond buildings

Improving access for persons with disabilities entails much more than just making good buildings. NOWPDP’s Shaukat says access has to be ensured in transportation, physical environment, information and public services.

Last year, a participant for a Special Olympics Pakistan (SOP) marathon left his house at 5:00am on his customised bicycle to reach the venue at 7:30am as he could not commute by bus, rickshaw or taxi. Sarah Amin Ali, an SOP officer, says people with disabilities are unable to leave their house and pursue jobs or get an education because our transport system is not inclusive. “People in the lower income bracket have the worst problem of inaccessibility,” she emphasises.

Rasheed of SYC initiative echoes the concern. “There’s so much focus on employment quota for people with disabilities but how will the person reach the place of work if our public transport is not accessible, if our buildings are not accessible,” she asks.

It might take up quite a few years for Pakistan to give complete access to persons with disabilities but Shaukat says someone has to start somewhere and public buildings is a good place. For its part, NOWPDP has done a review of major public buildings in Karachi and given recommendations to the government on how to ensure and improve accessibility for places like Board of Intermediate Education, Karachi railway station and Karachi airport.

The NADRA registration centre on Khayaban-e-Ittehad in Karachi. PHOTO: ZORAL NAIK; ARTWORK: AAMIR KHAN

For a better tomorrow

As people with disabilities are not facilitated to move freely, their visibility is limited in public giving the impression that they don’t really exist. “For a very long time, I thought I was the only wheelchair user in Karachi because I could not see anyone else,” SYC’s Rasheed shares. This absence in public has far-reaching effects as people with disabilities are ignored in research, academia and policy making.

To ensure public buildings are accessible to everyone, NED’s Dr Ahmed says there is a need for public awareness as well as an increased emphasis in educational institutions on international best practices. “There should be proactive campaigning by the civil society for sensitising the management of government buildings and asking them to readjust the structures,” he says.

Rasheed further urges people to see providing access as their personal responsibility and to start from their own house. “Building ramps does not even cost much. It is not a matter of money; it is a matter of mindset,” she says.

On our society’s indifference towards the need for accessibility, Rasheed says it is easier to be oblivious to this issue unless you or your loved ones go through the problem. “I have physical limitation by birth but this could happen to anyone after an accident or certain diseases. Why do we want to wait for that moment, why don’t we make efforts for everyone for the sake of humanity,” she asks.

Pointing out that even the so-called educated class in Pakistan is not fully conscious of the need, Rasheed says her movements are more restricted since she moved from PECHS to Defence – supposedly the poshest neighbourhood of Karachi – a decade ago. “Zamzama and Shahbaz in DHA have great places to eat and shop but I don’t go there because out of 50, only five are accessible,” she shares.

The fault, Rasheed says, is in the original planning which does not allocate space for ramps. “So now if someone decides to build a ramp, they have to encroach street space,” she says, wondering what one can expect from a common person if the educated class, architects and interior designers are not mindful of inclusivity.

Source: Tribune